William Stafford (1914-1993) grew up as a teenager in the Great Depression, and in a literary family. A conscientious objector, his poetry career was late starting, his first volume published in 1960. Notwithstanding, in his life he wrote over 22 000 poems, about 3 000 of which were published. He was a lecturer at the Lewis and Clark College in Oregon. His style is Robert Frostian, grounded, gentle, and wise.

William is one of those not well known poets, therefore tending to be overlooked, yet richly rewarding on reading. His most famous poem is Travelling Through The Dark in which he encounters an animal on the side of the road. Even now, my heart is in my mouth as I read the poem, unsure of the outcome. Please click on the link for a beauty. This poem below cuts to the very core of how we make momentous decisions in our lives. And in that most significant of all decisions – with whom we choose to spend most of our time. Not necessarily in marriage, also in our friendships.

A Ritual to Read to Each Other by William Stafford

If you don't know the kind of person I am

and I don't know the kind of person you are

a pattern that others made may prevail in the world

and following the wrong god home we may miss our star.

For there is many a small betrayal in the mind,

a shrug that lets the fragile sequence break

sending with shouts the horrible errors of childhood

storming out to play through the broken dike.

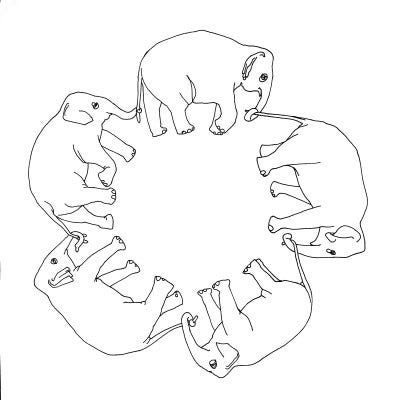

And as elephants parade holding each elephant's tail,

but if one wanders the circus won't find the park,

I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty

to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.

And so I appeal to a voice, to something shadowy,

a remote important region in all who talk:

though we could fool each other, we should consider—

lest the parade of our mutual life get lost in the dark.

For it is important that awake people be awake,

or a breaking line may discourage them back to sleep;

the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe —

should be clear: the darkness around us is deep.

It seems fairly obvious, doesn’t it? If we do not know each other at the point of marriage or committed friendship, all hell could break loose and we end up following patterns set by other people, not ourselves. Thus, ‘following the wrong god, we may miss our star’. But look at the rate of divorce statistics all around the world. Many people so little know the other that they fall into a paradigm of relationship that is injurious. ‘I must get married. I must marry that particular person’. Not for a special reason perhaps but for an ordinary reason – like ‘all my friends are getting married’ (other people’s patterns), or ‘I am lonely’, or ‘we have been together for years, surely we are right for each other?’ (the wrong god followed home). And family and friends are perhaps (should that be usually?) quite useless in challenging our choices, preferring to leave the responsibility of selection to the person involved (how can that work? the person involved may be the last person to know).

But if the die is cast, William hits a home run with the consequences. The small, perhaps trivial (and yet not at all trivial, rather hugely hurtful) shrug, the small betrayals ‘in the mind’. He knows how minds work, doesn’t he? If we did not know each other at the start (his original premise), we are at the prey of a whole range of misinterpretations later on. And a simile to complete the consequences. A dyke bursts, we know what that looks like, a sudden, immense rush of uncontrollable water. Except it is not water, no, it is ‘the horrible errors of childhood, sent out shouting and storming to play’. William’s language echoes the errors of adulthood when a relationship is breaking down – the shouting, the storming, the play in spent, muddy water.

To emphasise the point, William introduces a stunning simile. A circus troupe of elephants, connected trunk to tail moving towards the park where the circus tent is pitched. But if one elephant loses grip, loses contact, they are all adrift. So it is with a relationship meltdown, a series of habits seemingly secure in place until a link is broken. Then the eternal hammer: ‘I call it cruel and maybe the root of all cruelty/to know what occurs but not recognize the fact.’ How often do I see something happen (know what occurs) but do not understand the meaning (not recognise the fact)? The calm simplicity of William Stafford’s poetry is sublimely powerful.

We are approaching a crescendo. William appeals to a voice (he does not say whose or where, but we are still expecting some tie-in with the title - A Ritual to Read to Each Other, when is he going to talk about that?), a shadowy voice, in a remote region in all who talk (that is everyone, people, every single one of us are pinned in the headlight here). It is possible to fool each other, but at what cost? The parade of our mutual life gets lost in the dark. The voice is that important. ‘We should consider’ – notice he is not saying we must; rather he is asking for consideration, thoughtfulness, a sensitivity to the situation and the contained emotions.

Finally, William proacts by about eighty years to a prevalent style today – ‘wokeness’. If we are awake, then BE awake. Or the line of elephants breaking, the misinterpreted tone or gesture, the different pattern of communication between partners who are accustomed to each other, any of these items missed and we fall asleep again without noticing; we are not woke. His last words are crystal – ‘the signals we give — yes or no, or maybe — /should be clear: the darkness around us is deep’. Observe how insecure, how open to misinterpretation all our communication patterns are. A semaphore signal mistaken through the smoke may change the course of a war. A misheard conjunction can (at the right, or the worst, moment) destroy a relationship. Oh yes, the darkness around us is indeed deep.

And the title? Reading to each other is a great litmus test. Make it a ritual. It is hard, maybe impossible, to read to someone without them ‘seeing who you really are’. Perhaps this is why reading to children is such a good pastime – the children listen to the story – and ‘read’ the reader’s personality, their attitude, their care.

I urge all of you to begin a practice (unless already begun) of reading aloud – to your children, your grandchildren, your podcast microphone, and above all, to your love.

If you have not yet become a subscriber, I urge you to do so. I will be posting more content to subscribers only.

Ian