Is indifference a proven corollary to suffering? Auden finds a connection that is not obvious but once drawn to one’s attention is undeniable. There always seem to be some people who are indifferent to an outcome that others feel is worthy of outrage or wonder or applause. So, how indifferent ARE we? So irretrievably focused on self and selfish outcomes, so wrapped into our own cocoons of safety and comfort, that we pay little heed to strange, wonderful, remarkable happenings? Or perhaps we simply do not know, are not aware, are concentrating on something else, are actually fed up with other people trying to grab our attention that we deliberately turn away from them, whatever they have to say? Is Auden talking about inadequate communication between people? I read an article this morning about the importance of attention management; how it is crucial to control our resources of notice in a world becoming ever more ingenious at grabbing our attention.

A reflection on this masterful poem by WH Auden presents an opportunity for insight into the nature of human relationships. Here is the poem, Musée des Beaux Arts:

About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer's horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Breughel's Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

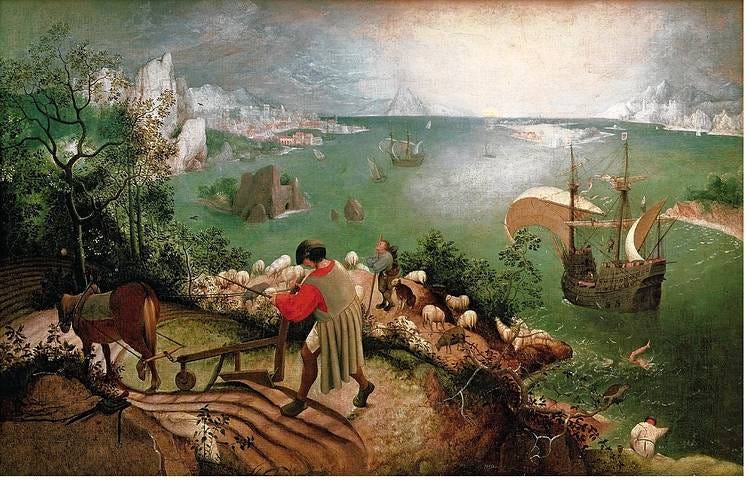

The painting Auden refers to is hanging in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Brussels, Belgium; it is titled Landscape with the Fall of Icarus and was painted by Pieter Breughel in 1558. The painting depicts the end of the myth of Daedalus and his son Icarus as told by Ovid, in which the father and son fashion wings for themselves to escape imprisonment, but Icarus flies too close to the sun and the wax on the wings melts, causing him to plunge to his death in the sea.

Auden is categorical: when amazing or awful things are occurring, there is always someone who does not really care. A boy flying across the sky and plunging into the sea; aged people waiting for a miraculous birth; a dreadful martyrdom; all these events and more are not noticed by everyone. A group of children skating on a pond; dogs and horses scratching their behinds; someone eating or opening a window or just walking dully along; a ploughman for whom the fall was not an important failure; and a delicate ship had to get on to its destination. Auden says the Old Masters were never wrong.

I am at a loss – and have been for many years – to reconcile this attitude with my (and my observations of other people’s) fellow feeling for their friends. We do love each other, we do care and take interest in each other’s achievements, we are not indifferent to others, we are compassionate beings. But then, why does the poem, in appearing to contradict the spiritual teaching of ‘love your fellow man and do unto others’, press so many green buttons of agreement?

The reality is that the poem is sometimes true. In part true, like much of our lives, a bit of this and a bit of its opposite. We can ignore the suffering of others, take little interest in marvellous happenings, actively seek to distance ourselves from trauma and pain, and pay no attention to uncomfortable truths about, say, malnutrition and infant mortality and climate warming. Not everyone and not all the time; but it happens. This may be why we admire missionaries so much, people who take on the burden of helping and noticing, and trust they are doing it on behalf of all of us.

Perhaps the parable of The Good Samaritan in Luke 10:25-37 can give me solace. If the separate parts of our beings are represented by all the characters of the parable, then we can sometimes pass by the injured man – like the priest and the Levite do in the parable – before that part of us that is compassionate – the Samaritan in us - stops to help.

This is a paradox for me, has been for years.